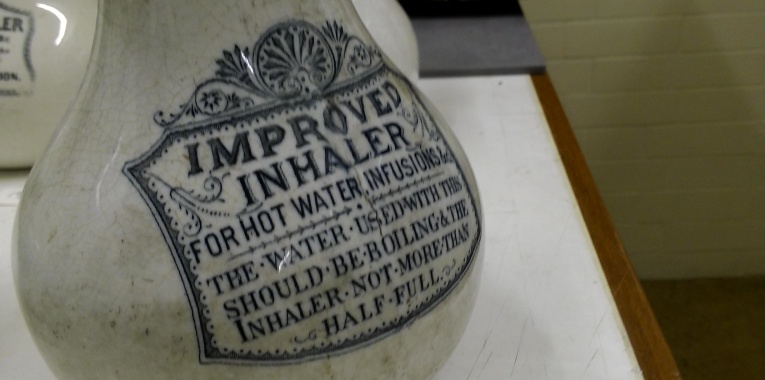

“Dr Nelson’s Inhalers” make up one of the largest single groups of historical inhalation and respiration devices in the Wellcome Medical Collection, currently housed at the Science Museum in London. Alongside other devices for treating pulmonary ailments like early nebulizers, nasal inhalers, and medicated cigarettes, there are 12 intact examples of the Nelson Inhaler of various designs, sizes, and age. This is testament to the popularity of the device and to its widespread availability in the 19th century. Likewise it is a sign of the growing need for reliable treatments as rapid urban development across Europe led to a peak in respiratory ailments like asthma and consumption. Simple inhalation devices like this had a profound impact on improving the lives of thousands of patients in the 19th century.

Environmental pollutants, industrial working conditions, and the spread of chemicals in middle-class consumer articles – even articles seemingly as banal as wallpaper – were a cause of almost constant suffering throughout the 1800s. In the Medical Times and Gazette, the London Fog in 1873 that killed 273 people as a result of bronchial complaints was reported as “one of the most disastrous this generation has known”[1] and Mark Jackson has reconstructed a series of communications in letters to the Lancet and other medical journals looking for cures for these environmental diseases.[2] Charles Dickens is only one of the most famous voices to speak of suffering from asthma in the nineteenth century. In a letter to his sister-in-law Georgina on 7th August 1857, he writes: “I have had an excellent night (a little opiate in the medicine) and have had no return whatever of the distress of yesterday morning”. Elsewhere, Dickens refers to fits of coughing early in the morning, so that the dramatic response to a dose of opium (laudanum) is diagnostic of asthma. In a letter he wrote to his daughter Mary, dated 29 March 1868, he writes: “I have coughed from 2 or 3 in the morning until 5 or 6 and have been absolutely sleepless. Last night I took some laudanum, and it is the only thing that has done me any good.”[3] Unveiled in 1861 and first marketed with an announcement in The Lancet in 1865,[4] “Dr Nelson’s Improved Inhaler” sought to provide a reliable form of therapy for pulmonary and bronchial ailments of this sort.

“Dr Nelson’s” was not the first inhaler in history, but it was revolutionary for its ease of use and patient-friendliness as well as for its industrial production, distribution, and widespread marketing. Like its immediate predecessor, the Mudge Inhaler, the Nelson device deployed the inhalation of steam to deliver medication directly to the lungs. Inhaled therapies had been used for the treatment of pulmonary conditions and psychotropic effects for well over 4,000 years, and the inhalation of vapours is documented in Egyptian, Indian, European, and East Asian texts. In the modern period inhalation became increasingly noted as a therapeutic form in the late-18th century, and John Mudge’s invention of a simple pewter inhaler in 1778 can probably be seen as the first widespread medical device for inhalation, at least in Britain. Its principle, like the Nelson Inhaler following it, was direct drug delivery using steam particles to transport diluted volatile substances to the trachea, bronchi, and lungs, where they were to be absorbed. The adaptation by Jean Sales-Girons of large scale droplet dispersers, then being used in thermal spas, to create portable nebulizers led to a renewed interest in steam inhalations for ailments like asthma and the croup in the mid-nineteenth century.

The inhaler was first presented at a meeting of the Royal Medical and Chirurgical Society on May 28th 1861 and was apparently the product of a medical practitioner’s empirical experience rather than applied scientific design.[5] The most likely inventor of the device was Thomas Andrew Nelson, who qualified in Edinburgh with a dissertation on “Phthisis pulmonaris” in 1834, before relocating to London where he lived and worked until his death in the area of Regent’s Park, at first in Wimpole Street, then in Nottingham Terrace off York Gate.[6] He was the only Dr Nelson who held a Fellowship at the RMCS in the period in question and it is notable that in the geographical area favoured by the Harley Street establishment, he was surrounded by highly-respected physicians and experts in respiratory disease and treatments like Sir Charles Scudamore, himself a leading member of RMCS. The RCMS offered a network with collective experience and the ability to empirically test the inhaler’s therapeutic efficacy.

“Dr Nelson’s Inhaler” was introduced to the market with some delay by S. Maw & Son Co. from their London base in Aldersgate Street in 1865. The decision of the inventor to work with Maw & Sons is also easily understood. The company was at the forefront of manufacturing and supplying medical equipment to British hospitals and medical practitioners in Victorian Britain.[7] Its reputation was such that it was featured in the 1862 Exhibition, where a range of its ceramic inhalers were displayed. Maw & Sons were particularly well suited to making ceramic instruments as John Hornby Maw (Charles’ uncle) left the business and was settled in Shropshire by 1850, where his new business designed and manufactured encaustic tiles first in Worcester, then in Brosely, and finally Benthall. With these family connections to the ceramics industry and their own manufacturing and marketing expertise, S. Maw & Son were an obvious partner with a reputation for quality.

“Dr Nelson’s Inhaler” was featured in The Lancet, The Medical Times and Gazette, and the British Medical Journal and became popular with self-medicators and professional physicians alike, playing no small part in the acceptance of inhalants for the first time in the British Pharmacopoiea in 1867. Its popularity can be seen in contemporary peer reviews by medics like William Abbotts Smith, who recommended the device from his clinical experience in the Finsbury Dispensary and the Metropolitan Free Hospital, which both treated London’s poor and most vulnerable bronchitic patients.[8] The device was one of the first suitable for the kind of commoditization of therapy and self-medication for which the wealthier classes in the era were renowned, and it also remedied some of the technical difficulties associated with inhalation therapies identified by contemporary critics. Given its relative ease of use, its clinically affirmed reliability, and its recommendation by leading practitioners and authorities of the day, it is unsurprising that “Dr Nelson’s Inhaler” makes up one of the largest single groups of historical inhalers in museum collections across Europe today.

[All images are the author’s own and are courtesy of the Science Museum London]

[1] Medical Times and Gazette. 1873 (20 December); 2: 369

[2] Jackson M. Asthma: The Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2009.

[3] The Selected Letters of Charles Dickens ed. Jenny Hartley. Oxford: OUP, 2012, 321; The Letters of Charles Dickens. Vol. 2: 1857-1870 ed. Mamie Dickens, Georgina Hogarth. London: Chapman and Hall, 1880, 377.

[4] The Lancet General Advertiser. 1865, 85 (2163): 152.

[5] Proceedings of the Royal Medical and Chirurgical Society of London 1858-1861; 3: 399.

[6] Graduations and Surgical Examinations. Edinburgh Medical and Surgical Journal 1834; 42 (121-Part III): 490; Royal Medical Chirurgical Society of London. Annual lists of fellows. Medico-Chirurgical Transactions 1861; 44: xxxii.

[7] Editorial: An historical company. Chemist and Druggist 1917; 89 (1947):42.

[8] Abbots Smith W. On Affections of the Throat and Lungs and their Treatment by the Inhalation of Gases and Medicated Vapours. London: Harry Renshaw, 1867: 22.